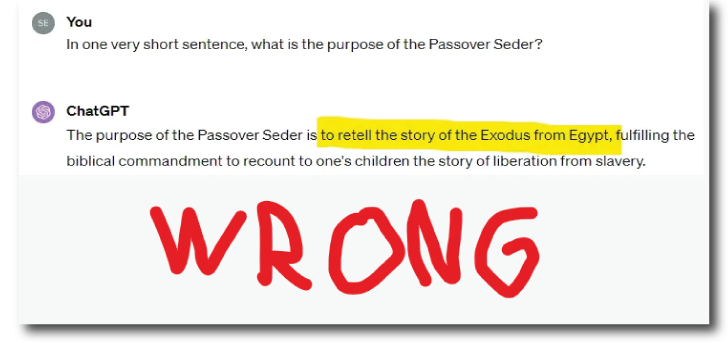

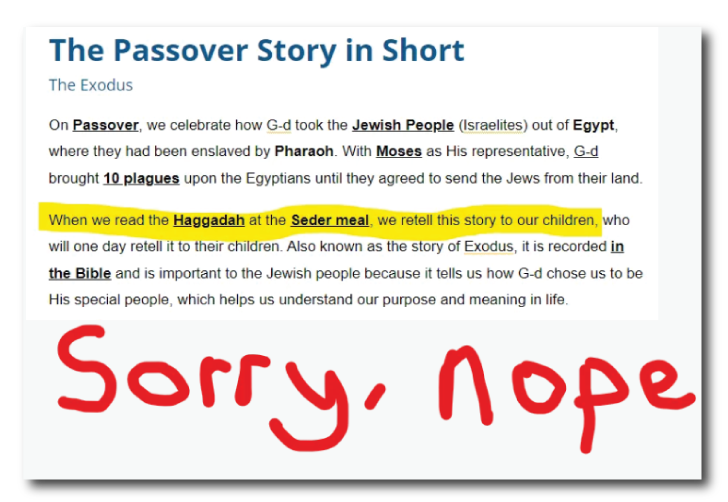

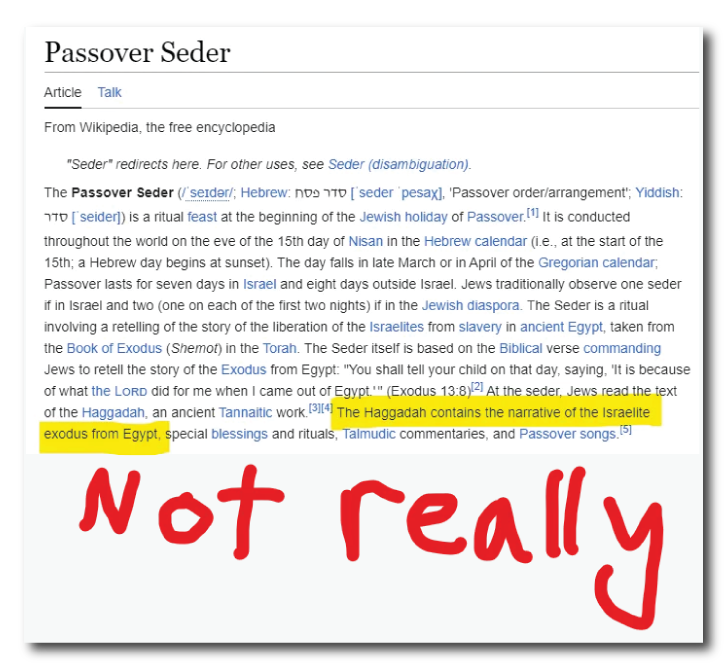

The most basic thing you think you know about the Passover Seder is wrong.

Stories have no point; stories are the point.

The tomb of the Capulets. ROMEO holds an unconscious Juliet in his arms, thinking her dead.

ROMEO

…Come, bitter conduct, come, unsavory guide!

Thou desperate pilot, now at once run on

The dashing rocks thy seasick weary bark!

Enter the PRINCE.

PRINCE

Romeo! Sorry to intrude. Real quick:

A glooming peace this morning soon will bring.

The sun for sorrow will not show his head.

Once you are dead, we’ll talk of these sad things.

Some shall be pardoned, and some punishèd.

For never was a story of more woe

Than this of Juliet, and you, Romeo.

ROMEO

Okay, then. Noted. Where was I? Oh yeah:

Here’s to my love. [Drinking.] O true apothecary,

Thy drugs are quick. Thus with a kiss I die…

— Not exactly William Shakespeare, hypothetical alternative version of Romeo & Juliet (V.3)

I hope you’re sitting down. I hope you don’t have a fragile heart monitor. Please don’t take a big sip of coffee right before reading the next sentence:

The Passover Seder is not about telling the story of the Exodus from Egypt.

And the traditional Haggadah does not, in any meaningful way, tell that story.

If you were (somehow) to arrive at a Seder not knowing the story of the Exodus, you would be utterly at sea. The Haggadah refers constantly to that story, but never, ever tells it.

Don’t believe me? Go to the video replay. Look in the traditional text of the Haggadah and find me The Part Where We Actually Tell the Story.

Much of the Haggadah isn’t even close to “telling the story.” Even in the “Maggid” section (“Maggid” means “Telling”), which seems like it really should tell the story, we get lots of material that manifestly doesn’t, from a story about five rabbis telling the Exodus story in B’nei Brak (but without doing the obvious thing and telling the story as a story within the story) to The Four Sons (always good for surfacing family drama in discussing reactions to the story, but not quite telling the story), and from Calendar Corner (are we two weeks late to this party about theoretically telling the story?) to Super Fun Rabbinic Math Time with Plagues (“let’s play with numbers in the story,” and if you like that sort of thing, this part is absolutely that sort of thing).

As I see it, there are only five even remotely plausible candidates for being The Part Where We Actually Tell the Story, and they are:

A one-sentence synopsis right after the Four Questions (“We were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt, and God brought us out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm.” The Haggadah then pivots immediately back to commentary.)

Two very broad paragraphs on the journey from idolatry to monotheism. (From “In the beginning, our ancestors were idol worshipers” through “And also that nation for which they shall toil will I judge, and afterwards they will go out with much property.”)1

The one-paragraph first-fruits declaration (with Rabbinic footnotes) that outlines the story in a very zoomed-out way,2 followed immediately by a glamorous close-up for the Ten Plagues;

The song “Dayyenu,” “Enough for us,” which is kind of a musical executive summary of many major parts of the story; and

A culinary theatre experience (Rabban Gamliel’s three things until the meal) that gestures to selected themes from the story and provides a few scattered, non-linear details.3

None of these — the very best candidates for being The Part Where We Actually Tell the Story — are truly “telling the story.” Put them all together and, at best — generously — what you have is a poor-quality, incomplete, chronologically mixed up synopsis.

Anyone want to challenge that? You think the Haggadah counts as “telling the story” of the Exodus? Okay, fine. I’m about to “tell you the story” of Romeo & Juliet. Here goes, in full:

“A boy and girl fall in love, but their families are fighting, so they end up dead. Now please enjoy a three-hour recitation of academic journal articles by Shakespeare professors arguing about historiographical methodologies for illuminating the historical context of this play.”

— The Story of Romeo & Juliet: The Haggadah Edition, Unabridged

Now you tell me: Did I just “tell you the story” of Romeo & Juliet? I would say no. I would say that to tell Romeo & Juliet, at minimum you need to touch on Verona, Montagues, Capulets, Tybalt, Mercutio, the Prince, Friar Lawrence, the opening fight scene, the balcony scene, the botched plan with fake poison, and how the final scene in the tomb goes down with first Romeo and then Juliet killing themselves. Oh, and by the way, you should probably also mention Romeo and Juliet’s names. And don’t you just want to include things like Queen Mab and “a rose by any other name”? Whether for emotional punch or just for literally understanding what happens, my “story” above doesn’t cut it.

Likewise, to tell the story of the Exodus you need, well… more than the Haggadah gives you. Here is a list (probably incomplete) of Exodus story elements that are missing from the Haggadah:

“And there arose a new king over Egypt who knew not Joseph…”

The birth of Moses

Baby Moses in a basket in the Nile, and being drawn out by Pharaoh’s daughter

Moses growing up in the palace

Moses killing an Egyptian

Moses intervening with fighting Israelites

Moses’ flight to Midian

Moses at the burning bush

Moses’ return to Egypt

Moses and Aaron confronting Pharaoh, with or without the line, “Let my people go”

The magic contests between Moses and Pharaoh’s magicians4

Pharaoh making the Israelites’ work even worse after Moses & Aaron first confront Pharaoh

Any of the other confrontations with Pharaoh, conversations between Moses and the Israelite leaders, or other events that happen in between plagues

Everything that happens in between the tenth plague and the splitting of the sea, including the cinematic chariot chase to the seashore where God puts a cloud of fire between the Egyptians and the Israelites

As feminists have noted, the women of the Exodus — Yokheved, Miriam, the midwives Shifrah and Puah, and Pharaoh’s daughter — are not mentioned.

But it’s not as if the gentlemen get top billing either; Moses and Aaron are each technically mentioned in the Haggadah — but in both cases, only offhand, only in passing, in prayer/Psalm contexts, with no detail, and not in a way that gives a reader even the tiniest inkling that these fellows had anything to do with the Exodus story!

These omissions are flabbergasting. We have the mother of all stories here, and we’re leaving out emotionally amazing and narratively load-bearing parts of it. Not only are we missing almost all the good songs from “The Prince of Egypt,” but also, in every way that matters, we’re missing the title character from “The Prince of Egypt!”

So I hope we can all now agree: The traditional Haggadah simply does not “tell the story” of the Exodus from Egypt. It refers to the story. It talks loads about the story. But “tell the story” is just not the Haggadah’s job. At the Passover Seder, we don’t tell the story. We don’t tell the story! And then we have the gall to go around saying that the point of the Seder is to tell the story.

This is something that used to bother me a lot about the Haggadah, in ways I couldn’t even articulate. It bothered me when I was a kid, resenting all the weird non-story stuff delaying the meal. It bothered me even more later, when I was a newly-religiously-observant adult, wanting so badly to have a Meaningful Spiritual Experience at the Seder and feeling confused and, frankly, let down by the contrast between my expectations of the Haggadah and its reality.

Are we doing the Seder wrong?

Then Esther answered Mordecai: “Go, gather together all the Jews that are present in Shushan, and fast ye for me, and neither eat nor drink three days, night or day; I also and my maidens will fast in like manner; and so will I go in unto the king, which is not according to the law; and if I perish, I perish. But this will definitely work.”

And Mordecai said, “It totally will. And everyone should celebrate that annually.” So Mordecai wrote these things, and sent letters unto all the Jews that were in all the provinces of the king Ahasuerus, near and far, to enjoin them that they should keep the fourteenth day of the month Adar, and the fifteenth day of the same, yearly, the days wherein he predicted that the Jews would soon have rest from their enemies, and the month which he predicted was about to turn unto them from sorrow to gladness, and from mourning into a good day; that they should make them days of feasting and gladness, and of sending portions one to another, and gifts to the poor.

— Not exactly the Book of Esther, hypothetical alternative version (with verses from chapters 4 and 9)

One unorthodox (and non-Orthodox) approach to this disconnect between Seder theory and Seder practice would be to say that our theory is correct and our practice incorrect — that the Seder actually should be about telling the story of the Exodus — and that, therefore, we should stop reading the Haggadah aloud at the Seder.

According to this approach, the Haggadah is not primarily a script, but rather a set of dramaturgical and production notes, and we should use the Haggadah to help us plan a Seder that would include much less of the text of the Haggadah itself. The Haggadah would guide us in setting up our symbolic foods and stage directions. We’d still read some of the text for liturgical parts, like Kiddush, Hallel, grace after the meal, etc. But the Maggid section of the Seder would be completely Haggadah-less. The Seder would have no “You might think from Rosh Ḥodesh,” no Bearded Bickerers in Bnei Brak, no Bonus Plagues of Rabbinic Math, and no Family Feuding with the Four Sons, unless your family happens to feud spontaneously.

Instead, we would, you know, tell the story. Of the Exodus. From beginning to end. Maybe we’d tell it in our own words. Maybe we’d pause the narrative to sing each song in “The Prince of Egypt.” Or perhaps, more conservatively, we’d simply read Exodus 1 through 15 aloud. It’s a magnificent read!

And it’s not as if we don’t have precedent for reading a Biblical text in order to fulfill a commandment to remember a story. Every year on Purim, we read the Megillah (The Book of Esther), out loud, verbatim, beginning to end. Nothing could be simpler than reading Esther at Purim — there’s no Seder, no leaving things out, no presenting things out of chronological order, no reciting obscure rabbinic commentaries — and not because obscure rabbinic commentaries don’t exist for Esther the way they do for Exodus (because boy do they!), but simply because our practice is to center our Purim observance on the Biblical text of the story rather than commentaries on that text.

So why isn’t the Passover Seder like reading Esther on Purim?! Why not just read Exodus?

I believe there is, in fact, a very good reason that we don’t.

In this case, as in so many others, our practice knows better than our theory. I believe this difference between how we tell the Purim story and how we tell the Passover story derives from the Bible itself.

And I will explain how in a moment. But first, a word from David Brooks.

What are stories for?

Recently, while browsing in the Museum of Modern Art store in New York, I came across a tote bag with the inscription, “You are no longer the same after experiencing art.” It’s a nice sentiment, I thought, but is it true?… Does consuming art, music, literature and the rest of what we call culture make you a better person?

…Aristotle thought it did, but these days a lot of people seem to doubt it. Surveys show that Americans are abandoning cultural institutions.… College students are fleeing the humanities for the computer sciences…

And yet I don’t buy it. I confess I still cling to the old faith that culture is vastly more important than politics or some pre-professional training in algorithms and software systems. I’m convinced that consuming culture furnishes your mind with emotional knowledge and wisdom; it helps you take a richer and more meaningful view of your own experiences; it helps you understand, at least a bit, the depths of what’s going on in the people right around you.

— David Brooks, “How to Save a Sad, Lonely, Angry and Mean Society”

I agree with David Brooks; great art can, indeed, make us better people. Even if I have doubts that an artist can use art to change people in any simple, linear way, I have no doubt that great art can be profoundly transformative.

And yet, I find myself feeling slightly put off by articles making this point, a species of which this (good) article by Brooks is only one specimen among many.

Art and culture improve us, but improving us is a side effect of art and culture, not their purpose. To ask why the arts and humanities should be funded, or whether and why people should spend time with them, and then pivot immediately to the (true) point that art improves us is a little like saying, “Why yes, I love my wife and children, because they improve my life and make me a better person.” For the record, that’s true about my wife and children — they make my life better and they influence me to improve myself — but that’s not what I would ever want to answer if someone asked me “why” I love them.

Any “reasons” given to a “why” question about love are, inherently, some combination of insufficient, imprecise, exaggerated, and dishonest. If prompted with a question like “Why do you love so-and-so,” we can all come up with answers — but we probably don’t (and certainly shouldn’t) believe them. We don’t love people for their instrumental “use” — that’s what Rabbi Dr. Abraham Twerski (of blessed memory) called “fish love.” No, we love people because they are themselves. We love them because we are in meaningful relationship with them. We love them because love is self-justifying. Love is not self-sustaining — it takes work to sustain — but, once in place, love calls on us with authority to do the work of sustaining it. “Love is not love / Which alters when it alteration finds.”

Just as people are not means to an end but ends unto themselves, the same is true of culture — of religion, of art, of stories.

Stories don’t have a point; stories are the point.

Telling the story of telling the story

REBEL WAR ROOM BRIEFING AREA.

DODONNA

…The target area is only two meters wide. It's a small thermal exhaust port, right below the main port. The shaft leads directly to the reactor system. A precise hit will start a chain reaction which should destroy the station. Only a precise hit will set up a chain reaction…

WEDGE

That's impossible, even for a computer.

LUKE

It's not impossible. I used to bull's-eye womp rats in my T-sixteen back home. They're not much bigger than two meters.

DODONNA

Man your ships! And may the Force be with you! Also, by the way, the Force told me that what you are about to do will succeed, and here is how your descendants should commemorate it in every future generation: First, they should quote lines from what we’ve been saying at every opportunity. Second, they should buy a lot of merch with our faces on it. Third, there should be conventions where people get together and dress up like all of us…

— Not exactly George Lucas, hypothetical alternative to a scene in Star Wars IV: A New Hope

Many stories refer to themselves explicitly as stories, or marvel at how far in the future they (as stories) will be told. But this part almost always comes as a denouement, if not an afterthought.

“For never was a story of more woe,” says the Prince of Verona, “Than this of Juliet, and her Romeo.” He says this as the final couplet of the play, after all the action is concluded, and not, as in my alternative version that began this post, just before Romeo’s suicide. In the Book of Esther, too, Mordecai and Esther write the story they’re living, sending the Book of Esther to Jews throughout the Persian Empire and founding the holiday of Purim. But they do so after Haman’s attempted genocide fails and the battles are all won — not (as in my hypothetical version above) just before the climactic action of Esther intervening in court politics at the risk of her life. Nor, indeed, does Luke Skywalker turn to the camera just before attacking the Death Star and invite viewers to come say hi at ComicCon.

I belabor this point to emphasize the profound strangeness of the Book of Exodus.

Like many other stories, Exodus is a story that refers to itself. But unlike other stories, Exodus places that self-reference as a story directly at the heart of the plot. The Exodus as a story echoing down the generations is not a denouement to that story; it is the climax of the story.

Let’s drop into that story, in medias res. It is chapter 10 of Exodus. Nine plagues have struck Egypt, and Pharaoh has sometimes acquiesced to Moses’ demand of liberty, but always changed his mind afterward.

Pharaoh said to him: Go from me! Take you care: You are not to see my face again, for on the day that you see my face, you shall die!

Moshe said: You have spoken well; I will not henceforth see your face again!

YHWH said to Moshe: I will cause one more blow to come upon Pharaoh and upon Egypt; afterward he will send you free from here. When he sends you free, it is finished—he will drive, yes, drive you out from here.

God tells Moses the people should “borrow” wealth from their Egyptian neighbors, and promises that the Egyptians will agree. Moses tells Pharaoh that God says:

In the middle of the night I will go forth throughout the midst of Egypt, and every firstborn shall die throughout the land of Egypt, from the firstborn of Pharaoh who sits on his throne to the firstborn of the maid who is behind the handmill, and every firstborn of beast. Then shall there be a cry throughout all the land of Egypt, the like of which has never been, the like of which will never be again. But against all the Children of Israel, no dog shall wag its tongue, against either man or beast, in order that you may know that YHWH makes a distinction between Egypt and Israel. Then all these your servants shall go down to me, they shall bow to me, saying: Go out, you and all the people who walk in your footsteps! And afterward I will go out.

He went out from Pharaoh in flaming anger.

Moses and Aaron now go to prepare the Israelite people for the final, terrible plague, and for their flight to freedom. And it is here, just before the tenth plague, that the climax of the Exodus story becomes a strange trance — a blurring of the boundaries between the experiencing and the telling; a meditation on its own story-ness; a meeting of the future and the past.

God tells Moses and Aaron that this spring month will now be the beginning of the Jewish calendar — an allusion not just to this one event but to its commemoration for all time. God tells the Israelites how to make the Passover offering, how to cook it, how to eat it, how to mark their doors for this one terrible night. But God then moves again from the now into the forever, saying:

Now this day shall be a remembrance for you; you are to celebrate it as a pilgrimage-celebration for YHWH; throughout your generations, as a law for the ages you are to celebrate it! For seven days, matzot you are to eat; already on the first day you are to get rid of leaven from your houses, for anyone who eats what is fermented—from the first day until the seventh day—: that person shall be cut off from Israel!

Within the story, God turns His eyes from ancient Egypt toward our kitchens, here in 2024. God names this holiday, within its own origin story, as a festival.

Moses passes along these instructions, and, following God’s example, speaks not only of the part played by his own generation, but of our time as well:

You are to keep this matter as a law for you and for your children, into the ages! Now it will be, when you come to the land which YHWH will give you, as he has promised, you are to keep this service! And it will be, when your children say to you: What is this service to you? then say: It is the sacrificial-meal of Passover to YHWH, who passed over the houses of the Children of Israel in Egypt, when he dealt-the-blow to Egypt and our houses he rescued.

The story pivots back to that one night and that one generation:

Now it was in the middle of the night: YHWH struck down every firstborn in the land of Egypt, from the firstborn of Pharaoh who sits on his throne to the firstborn of the captive in the dungeon, and every firstborn of beast. Pharaoh arose at night, he and all his servants and all Egypt, and there was a great cry in Egypt, for there was not a house in which there was not one dead.

He had Moshe and Aharon called in the night and said: Arise, go out from amidst my people, even you, even the Children of Israel! Go, serve YHWH according to your words: even your sheep, even your oxen, take, as you have spoken, and go! And bring-a-blessing even on me!

Egypt pressed the people strongly, to send them out quickly from the land, for they said: We are all dead! So the people loaded their dough before it had fermented, their kneading-troughs bound in their clothing, upon their shoulders.

The Israelites now bear the wealth of Egypt; they leave and begin their travels; they bake their matzah; and the narration notes that this is the end of the 430 years in Egypt that had been foretold to Abraham.

And then, yet again, God turns His gaze from the Exodus to our Seder night this year:

It is a night of keeping-watch for YHWH, to bring them out of the land of Egypt;

that is this night for YHWH, a keeping-watch of all the Children of Israel, throughout their generations.

God then gives laws for all future Passover observances, even now that the original Passover night has just passed. I stress again, in the story we are not approaching some anniversary of these events; we are not even yet at the shore of the Sea that will be split; the climax of the story is still happening in its original instance, but the Torah is already concerned with the laws for commemorating it:

And you are to tell your child on that day, saying: It is because of what YHWH did for me, when I went out of Egypt. It shall be for you for a sign on your hand and for a reminder between your eyes, in order that YHWH’S Instruction [“Torah”] may be in your mouth, that by a strong hand did YHWH bring you out of Egypt…

…And it shall be when your child asks you on the morrow, saying: What is this? you are to say to him: By strength of hand YHWH brought us out of Egypt, out of a house of serfs.

Not once, but again and again, in the climax of Exodus, God and Moses turn their eyes from the scenes before them in Egypt to make eye contact with us who sit at the Seder. Not afterwards, but from the heart of the action, they speak directly to us. They speak to each other of us.

We do not tell the story of Moses at Passover; Moses tells the story of us. We do not tell the story of the Exodus at Passover; God, by telling His Exodus story, speaks us into being.

At the Seder we are not reenacting something from back then, but enacting it now, in its first and only time happening. We are, in the most literal possible sense, central characters of the extended story of the Exodus from Egypt, and we are mentioned explicitly as such in the text of the story.

And that’s why the traditional Haggadah gets it right. In what it includes, and even in what it omits, the Haggadah hints to us what the real story is. The Four Sons; the five rabbis in Bnei Brak; the first-fruits declaration; the Sages delighting in math word problems about plagues — all these have a shared focus not on the tale, but on the tellers and the act of storytelling. The Haggadah follows the lead of the Book of Exodus and tells the story of telling the story of the Exodus.

And that story of the story — that’s the real story. The liberation from Egypt is just backstory; Moses, Aaron, Miriam, the burning bush, the magic contests and “Let my people go” — all that is purely optional exposition. The heart of the story being told at the Seder is the Seder itself — each Seder, each family, each year, and all of them on and on into forever.

Epilogue: Why Do You Like Stories?

In preparation to write this post, I asked each of my three children the same question: “Why do you like stories?”

The Wise Daughter (9) said:

“Well, it depends what time. Sometimes I like them because it’s just a complete escape from all reality. Sometimes I like them ‘cause they’re just entertaining. Sometimes — at the table, when we’re eating — I just like them because I can’t eat without reading.”

The Wicked Assertive Daughter (about to turn 7) said:

“Because stories make me feel good.”

My favorite answer was the one given by The Simple Son (about to turn 4). He didn’t say a word. He just gave me a look — not quite a withering look, but one that was part disapproving, part uncomprehending — it was a look that implied something like, “What?” or, “Are you speaking Romanian?” or, “Why did you just ask me to colander barbecue pants?”

His look told me that I was being the Son Father who Did Not Know How to Ask a [Reasonable] Question.

Our lives are stories; stories are life. A story is a world. A story is a journey that is its own destination.

If you have to ask what a story was “for,” it was never a story worth telling.

The idolatry to monotheism narrative is an alternative vision of what “the story” is that we’re supposed to be telling, based on an argument between two sages. The first answer (Candidate #1 above) is a micro-telling of Shmuel’s version — a story of going from slavery to freedom — and this (Candidate #2) is Rav’s version — a story of going from idolatry to monotheism. But does this text “tell” Rav’s version of the story? If we’re telling the story of idolatry to monotheism, then, frankly, this is a pathetic draft. We should hear the whole Abraham character arc, not a few snippets; we should hear vastly more of the Exodus; we should end with the climax of the giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai. So even given a different definition of the story, I would call this just a sketch, a mere gesture toward the story.

“A wandering Aramean was my father, and he went down into Egypt, and sojourned there, few in number; and he became there a nation, great, mighty, and populous. And the Egyptians dealt ill with us, and afflicted us, and laid upon us hard bondage. And we cried unto the LORD, the God of our fathers, and the LORD heard our voice, and saw our affliction, and our toil, and our oppression. And the LORD brought us forth out of Egypt with a mighty hand, and with an outstretched arm, and with great terribleness, and with signs, and with wonders.” (Deuteronomy 26:5-8.)

The first-fruits declaration is, like the other candidates, a very high-altitude summary of the Exodus. It doesn’t take us on a full journey, it just shows us the map. Now, the Haggadah adds some commentaries and prooftexts to this declaration, and in the course of those comments, a few more narrative details come out, such as:

That Israelite slave labor built the storage cities of Pithom and Ra’amses;

That marital (sexual) relations ceased between Israelite husbands and wives at a certain point due to the conditions of slavery;

That there was a decree to kill firstborn Israelite boys; and

That God performed the tenth plague killing Egyptian firstborns Himself, and not through an angel.

Still, all this is by no stretch of the imagination a real “telling” of the story.

Rabban Gamliel tells us three things that absolutely must be in our Seder. In the course of discussing prooftexts for this, we get a few more morsels of narrative detail, such as:

The part where God passes over Israelite homes on the way to smite Egyptian firstborns in a way that has something to do with the Passover offering (although the full details of how this worked, with blood on lintels etc., is not given);

The bit where the dough didn’t have time to rise, hence we’re eating matzah now;

The fact that the maror (bitter herb) represents the bitterness of slavery.

Then we get the famous part where in each and every generation, we must all see ourselves as personally having come out of Egypt. (This part is an absolute banger and very moving, but it isn’t telling the story, it’s telling us how to experience the story, not the story.) Then we sing some Psalms; drink some wine; wash our hands; and have more immersive culinary theater with matzah, bitter herbs, ḥaroset, and the concept of sandwiches. And then we eat the meal, and frankly, all but the true die-hards go home or go to bed at that point (not me, of course, I’m a die-hard), and there are prayers and songs after the meal, which I’m not going to go through here, but read them yourself and believe me — they don’t tell the Exodus story.

Yes, the magicians are quoted in passing during Super Fun Rabbinic Math Time with Plagues, but the actual magic contests go completely untold.